William H. Russell was looking to grow. His stagecoach company was making him money, but he was limited mostly to passengers and their belongings. This made the westward crossing from St. Louis to San Francisco 3-weeks in length.

But there were also important documents and communication being carried as well. Remember, this was before the telegraph had wide distribution and use in the west. This is when Russell wen to CA Senator William Gwin. Gwin was anxious to speed up communication and transportation for his state.

Westward extension of the telegraph and railroad had been encouraged for years but with no result. Gwin hinted that Russell might be able  to win away the $600,000 mail subsidy from a competitor if Russell’s company could substantiallNEWy shorten the existing three-week mail delay. Russell set out to demonstrate he could cut the mail delivery time to 10 days with a “pony express.”

to win away the $600,000 mail subsidy from a competitor if Russell’s company could substantiallNEWy shorten the existing three-week mail delay. Russell set out to demonstrate he could cut the mail delivery time to 10 days with a “pony express.”

He and his partners gambled they could win government freighting contracts before a transcontinental telegraph line was built. The company already operated a freight and coach line to Salt Lake City. However, many more stations, riders, horses and equipment would have to be assembled within 60 days – and all would have to mesh perfectly – in order to meet a deadline set by Sen. Gwin.

To find the riders, Russell placed advertisements in western newspapers:

“WANTED – Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over 19. Must be expert riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred.”

From the many applicants, Russell hired 80, none weighing more than 130 pounds. In the next few months, Russell hired an additional 40 riders as experience indicated arduous routes had to be shortened. The pay was $125 a month plus bed and board – equivalent to about $30,000 a year in today’s currency – and a fabulous salary for horsemen of that day.

For his riders, Russell purchased 500 small, tough mustangs at an average price of $200 each. This was four times the price of an ordinary riding horse, but the mounts chosen had to have extraordinary endurance.

The “dash” horses were branded XP (for express pony) on their right flanks. They were fed grain freighted in at great expense. Grain-fed horses had greater speed and endurance than grass fed animals such as those of Indians. Barrels of water also were shipped to stations that did not have a well or access to a stream.

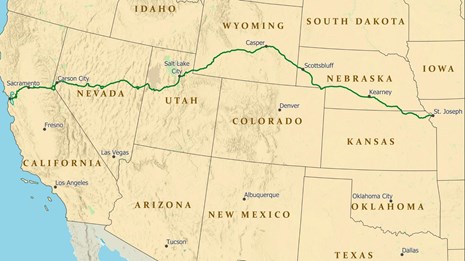

The route from St. Joseph, Missouri, to San Francisco, was established with 157 stations divided into five divisions. Each division “home” shelter had a superintendent, bunks, a cook, supplies and extra horses. In between division stations there were “relay” stations consisting of two men and two horses.

Riders rode from home station to home station. The distance varied from 40 to a 100 miles or so — depending on terrain. At each relay station – 7 to 20 miles apart — two attendants had not more than two minutes to transfer the light-weight saddle and four, built-in mail pouches to a fresh mount.

Riders rode from home station to home station. The distance varied from 40 to a 100 miles or so — depending on terrain. At each relay station – 7 to 20 miles apart — two attendants had not more than two minutes to transfer the light-weight saddle and four, built-in mail pouches to a fresh mount.

Meanwhile, the rider gulped a cup of black coffee and a few bites of a meat sandwich while stamping stiffness from his legs.

The system was reset by return mail from San Francisco. Mail to San Francisco was dispatched from New York City at 4 p.m. Tuesdays, and 2:30 p.m. Saturdays. The first leg was an eight-hour train trip to St. Joseph, Missouri. Here, the Pony Express began its 10-day dash to California.

At first, the mail charge was $5 per half ounce – a steep price for those days. After a couple of months, the charge was reduced to $1. This increased volume but reduced income. The Pony Express lost money throughout its short existence.

Pony Express riders were instant celebrities. Johnny Frey received a brass-band send off from St. Joseph with the first pouch. Two that became most famous were Robert “Pony Bob” Haslam and William Cody. The latter became better known as “Buffalo Bill” – star of a Wild West” road show.

Pony Bob set the record for endurance with a series of rides during the Washoe County War. Indians had killed one station keeper and stole the horses there and others in the division. He rode into his home station after covering 384 miles on horseback in 36 hours.

Unfortunately, the splendid and brave performance of the Pony Express came to naught. Two months after the Pony Express started, Congress appropriated funds to build a telegraph line to California. Under the impact of war necessity, the line was completed Oct. 24, 1861 – eight months ahead of schedule.

NEW ITEM ALERT! Marketing Tip Reader’s Only Special

We can also do the entire implementation and fulfillment for you, just give us a call at (360) 761-7486 and mention this post and we’ll be sure you get your 15% discount as well. You can also reach us here.

Add Your Comments